Stollmeyer Estate: Keeping Pace With Cocoa Through the Generations

By Rhonda Chan Soo | For Cocoa Research Centre, The UWI

For many Trinbagonians, the name Stollmeyer may be associated with its most visible artefact, a curiously ostentatious castle. Commissioned by Charles Fourier Stollmeyer and finished in 1904, Stollmeyer’s Castle (originally “Killarney”) is the first of the country’s “Magnificent Seven” to be completed and lived in. These majestic buildings line the Queen’s Park Savannah, a large recreational park in the center of the capital city that lays claim to being one of the largest traffic circles in the world. For others, the name Stollmeyer is inextricably linked to coconut water. Charles Fourier’s father, Conrad Frederick Stollmeyer, was the first in the family to come to Trinidad during the Industrial Revolution. A strict teetotaler, he attempted to provide an alternative beverage to rum, sending coconuts from Cocorite to Port of Spain in donkey carts, and earned the reputation of having started the country’s coconut water trade. For many others, the legacy of the family runs even deeper still. We venture to the Stollmeyer Estate, into the pulse of the cocoa bearing lands of the lush Santa Cruz Valley to learn more about the family’s history in cocoa, and the next pages of their cocoa story.

The Stollmeyer Estate is the kind of place where the hums of nature still beat out the sounds of screeching tyres and car horns, only faintly audible from the other side of the estate’s thick wall of foliage. The estate is looked after by Charles Merry, the great, great grandson of Conrad Frederick Stollmeyer. Warm and unmistakably humble, Charles was one of the last to grow up at the castle in Port of Spain. A walking encyclopedia, he possesses a wealth of knowledge not only on his family’s history, but also of the history of cocoa on the island.

Charles Merry shows me an excerpt from his grandfather Charles Conrad’s diary, detailing memories of the family’s two-year stint in Belmont: riding to school with his brother on a donkey, bathing in a small river that ran through the property, his father’s anguish at the death of his younger brother, his mother’s wish to leave the district, and his father, Charles Fourier’s initial purchase of land in the Santa Cruz Valley in 1883. At the end of that year, Charles Fourier had moved his wife and children to the Mon Valmont (“My Mountain Valley”) Estate in Santa Cruz, a partly derelict cocoa estate where Charles Fourier became interested in cocoa growing. He purchased additional estates in the valley, including La Deseada and La Regalada. Eventually the family would own the whole river bed from the Curacaye to the Barracks. Recognizing the inadequacy of absentee ownership, Charles Fourier called his sons back from England and designated them as managers on the estates. By 1906, both sons were married and each received cocoa estates. Albert Victor took up residence at Mon Valmont, and Charles Conrad was to reside at Killarney (“Stollmeyer’s Castle”). Following Charles Fourier’s initial investment in cocoa, Charles Conrad and Albert Victor built Stollmeyer into one of the largest producers of cocoa in the country.

Charles Merry tells me he knew from an early age that he wanted to be a cocoa farmer. He recounts: “Well, what happened, I was Charles Conrad’s eldest grandson, so from the time I was born, I was dragged up here to Santa Cruz, and put on a horse and taken round the estate, and I caught the bug kind of thing, cause it’s like a virus [laughs]. You can’t get it out of your skin, and I’ve always loved the country and working in crops, various crops.” He is presently about the same age that his grandfather Charles Conrad was when he sold off his estates to his children, “old and tired”, Charles suggests with a hearty laugh, and presumably fed up of the cocoa business. Charles Conrad saw the estate through some of its hardest times, when the notorious Witches Broom disease in the 1920s, followed by acute labour shortages during the war years, dealt Trinidad’s cocoa industry a blow from which it has never fully recovered. Whereas Trinidad used to export 35,000 tonnes of cocoa in the 1920s, Charles notes that the country barely made 500 tonnes in 2018.

When Charles Merry came back to the Stollmeyer Estate in the 1960s to run the estate’s operations, he was armed with a postgraduate degree from ICTA (forerunner to the UWI) and Oxford and years of work as an agronomist in sugarcane at Caroni Ltd. He admits that cocoa is a difficult crop, susceptible to changing weather and other unpredictable factors, and is also extremely difficult to come back after a blow. The estate seems like a large-scale laboratory in which the former agronomist is in his element, keenly interested in the cocoa varieties and how they perform. On a corner of the estate is a small drying house, no bigger than five by seven feet, with walls and a roof fashioned from a sheet of clear plastic. Charles Merry is experimenting with a new drying concept to see if it will yield improved results. Down in the processing area, he shows off large wooden boxes that he built in the 60s, still in use for the fermentation process. He explains that the precursor of the chocolate flavour develops during fermentation, and finishes in the drying process. He tells me that the flavour depends on how good you are. Over at the old-fashioned wooden cocoa house, he uses a simple pen knife to cut open a bean that is being sun-dried and points out subtle variations in purplish and brown hues, the differences largely imperceptible to an untrained eye.

Charles Merry on Stollmeyer Estate at their traditional cocoa drying house.

Glancing down the driveway of the estate house at La Regalada, Charles Merry recounts memories at the Stollmeyer Estate. He shows me an old “pay hole”, which has been removed from the former estate office and erected just outside it, as part makeshift fence, and perhaps part monument. During the 1960s, the productive cocoa land at the estate was around 400 acres, already down by half of the original 800 acres of the late 1800s and early 1900s when his grandfather and granduncle had taken the helm. Regardless, pay day in the 60s was a lively event that took place Fortnightly on a Friday. Families who worked with the estate would get dressed up and proceed to the estate office at La Regalada, down this very driveway which then was lined with vendors selling everything one could possibly need or imagine, from food to hair combs.

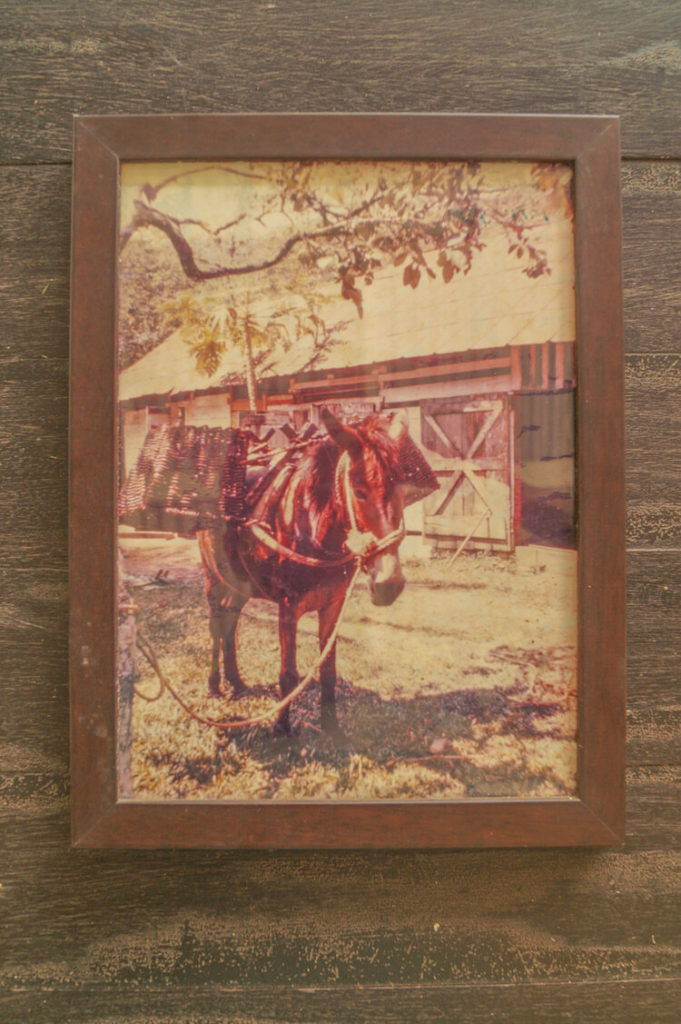

When asked about dancing cocoa, a folkloric image that has been ingrained into Trinidad’s collective subconscious, Charles Merry explains that they don’t regularly dance the cocoa anymore. Buyers now utilize their own equipment to shell and clean the dried beans. They are primarily interested in what’s inside the bean, its flavour. The last four years, the estate’s beans have been to a prestigious International Cocoa Awards competition of the Cocoa of Excellence Programme in Paris at the Salon du Chocolat, where they ranked among the top 50 in the world in 2015. The other changes at the estate have also been of a practical nature. Tractors have phased out the mules and donkeys once mounted with the harvested crop. Whereas women used to carry round baskets to collect and pick the pods, the spacing of the trees has also changed to accommodate a tractor moving between them. Apart from these technological innovations, coupled with minor tinkering, processing at the estate has remained remarkably much the same in Charles’ lifetime, as he met it.

Left: View down the driveway at La Regalada. Estate workers would receive their pay through this old “payhole”, which has been removed from the former estate office, and placed just outside it. | Right: An old photograph taken in 1963/64 of a mule called Christmas, born on a Christmas day. Tractors have now replaced the mules and donkeys once mounted with laden samboa baskets.

Left: Exteriors of buildings where the harvest is fermented and stored. | Right: Workers at the Stollmeyer Estate prepare a fermentation box, lining it with banana leaves. This box was built in the 60s, when Charles Merry first took over operations at the estate.

The estate is also home to some of the very first and historic Trinidad Selected Hybrids, TSHs, produced in Trinidad in the 1960s by cloning disease-resistant varieties of cocoa from the Amazon with “ICS clones”, clones of the Imperial College Selections that were then being propagated at Government stations. The ICS is the world-renowned Trinitario (“From Trinidad”) bean, a native variety produced through natural cross pollination of the delicate and flavorful Criollo (“Creole”) brought to Trinidad by Spaniards in the 1500s, together with the hardier Forastero (“Foreigner”), both varieties originating from the Amazon. Charles and his team of 100 workers first began the task of replanting the Stollmeyer Estate by interplanting the existing ICS clones with these improved TSH varieties. Charles tells me that he eventually mustered the courage to clear everything with a bulldozer and start over. The estate was then replanted using only the improved TSH varieties. Charles estimates that no more than 15 to 20% of the trees on the estate are from this first batch of TSHs. While some of these are bearing well, those that are not producing will soon be replaced with newer varieties. There are currently 100 acres in active cocoa production on the estate, maintained by 15 workers.

Out in the field, a man sits on a fallen log, cut branches spread before him in a seemingly haphazard array. He is calmly smoking a cigarette. Tom Lalloo has just about finished his work for the day but he graciously obliges in giving a demonstration. Using his cutlass he prunes a small cocoa tree, guiding the tool like a skilled swordsman, precisely nipping off branches at just the right angles to encourage new growth. In less than 60 seconds he effortlessly demonstrates the art form of pruning, which is being lost and slowly forgotten. Charles laments the difficulty of finding skilled labour like Tom who know how to handle the delicate operations of pruning and reaping.

Left: Tom Lalloo skilfully demonstrating pruning, an artform that is being lost through the decades. | Right: Charles Merry points out where the cocoa pod needs to be harvested, in just the right place with a sharp instrument.

Tom has been working with the Stollmeyer family for 40 years, having received his introduction to the crop as a small child accompanying his parents into the field. Tom’s father and grandfather before him also worked with the delicate crop. Some of the other workers on the estate go back even further than Tom’s family, as far as five generations. In addition to providing salaries, Charles is able to offer incentives such as small cottages as homes for the workers, who are able to leave the estate by midday should they want to pursue other work. He explains that this has helped with retaining workers. Throughout the years, however, as people gradually stopped working on the estate, Charles would not replace them, so the number of workers has fallen along with Trinidad’s shrinking agricultural sector.

A small residential cottage on the Stollmeyer Estate.

This past year, in 2018, the crop yield at the estate fell short of the usual nine to ten tonnes. Of the six tonnes harvested, five were shipped to Switzerland, and one to local chocolatiers at Cocobel. Although drawn to cocoa largely due to his love of crops and the countryside, Charles’ motivation for returning to it is a pragmatic one. He had taken a hiatus for 40 years, rearing cattle in Venezuela as a cowboy, but that is another story. Trinidad is now one of 17 countries in the world producing fine or flavour cocoa, which receives premium prices. Charles tells me he felt encouraged and supported by the Cocoa Research Section of the Research Division of the Ministry of Agriculture, Land and Fisheries, and the Cocoa Research Centre of The University of the West Indies, which has close to 90 years of continuous cocoa research, more than any other institution in the world. Even as other parts of the estate may move towards urbanization, Charles hopes to keep the valley flats in cocoa cultivation. With good cocoa soils and national talks of future development for the industry, Charles notes that there is a huge space for improvement. He and other cocoa producers are working to reframe the narrative and are eagerly writing the next chapters for cocoa in Trinidad and Tobago.

The storeroom will be filled with dried beans as the year progresses.

Left: An old scale, still fully operational. | Right: Beans from the Stollmeyer Estate, fermented, dried and ready for export.

Works Consulted:

“Mon Valmont Estate Santa Cruz” in Great Estates of Trinidad

“The Age of Reconciliation and the Magnificent Seven” by Michael Anthony in The Making of Port of Spain

“The Origin of the coconut vendor”:

http://www.guardian.co.tt/article-6.2.421688.5c6808293c

“Conrad Freidrich Stollmeyer” by Dr. Selwyn Cudjoe:

http://www.trinidadandtobagonews.com/blog/?p=11076

Interview with Charles Merry, November 2018

Excerpt from Charles Conrad’s diary, provided by Charles Merry